Looking for all Articles by William Goldsmith?

Top tips for switching genre and writing middle grade

Writer and illustrator William Goldsmith shares everything he learned when making the transition from graphic novels for adults to middle grade adventure stories

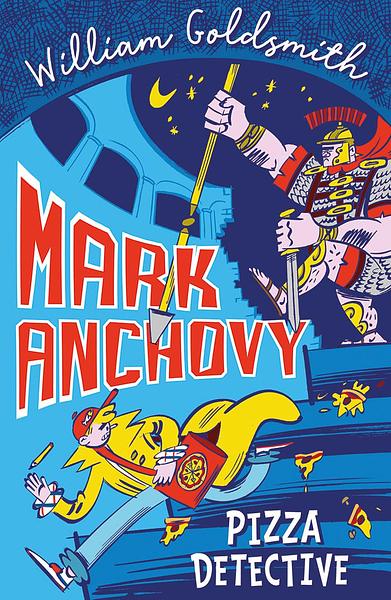

In 2016, I began writing a middle grade adventure story. The result was Mark Anchovy, pizza delivery boy and aspiring detective.

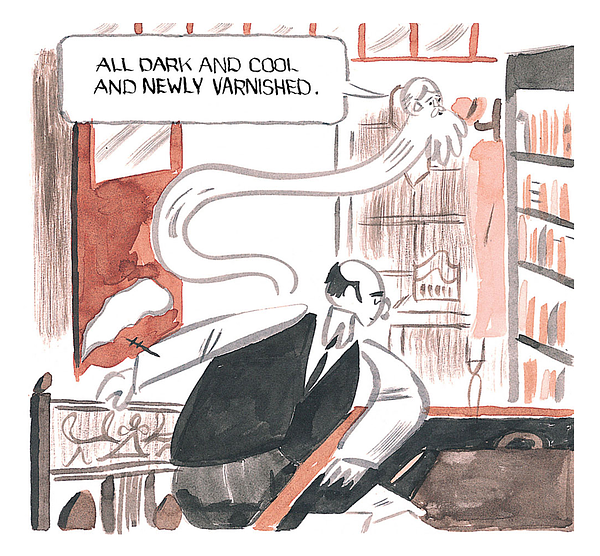

My previous medium was comics, which I loved for their creative freedom. But as well as being incredibly time-consuming, text in comics is costly. Word balloons often contain just three or four lines. Compared to the space for the image, it’s a squeeze.

I learnt this through my graphic novels, Vignettes of Ystov and The Bind. Although aimed at adults, these featured children, who schemed and observed as they wandered around their surroundings – be it an Eastern bloc city or a haunted bookbindery. The kids were my favourite characters, but in comics-form they got so few lines. This was my spark to switch medium: to give my child characters a bigger voice, via the more text-heavy format of middle grade.

I’m drawn to films and books with children who wander and observe, like the kids in Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle, or the eponymous sleuth in Erich Kastner’s Emil and the Detectives. The child-detective genre is well-worn, but it allows a character to roam, studying each case. When I moved opposite a pizzeria in Glasgow, I had it: an all-seeing child detective who also delivered pizzas. Mark Anchovy.

The process

I drafted an adventure story for both the child I was and the overgrown child I still am. I mashed together Ancient Rome, stolen renaissance art, secret societies, wisecracking bosses, Heath-Robinson gadgets. And pizza.

To gauge the right language, I read a lot of middle grade. I also applied to the Scottish Book Trust’s mentorship scheme. This paired me with award-winning children’s author Pamela Butchart, who helped me to sharpen the focus on adventure and humour.

Switching from slow, poetic comics for adults, to madcap adventures for readers aged 8-12, I learnt:

- First Draft: after plotting key scenes, write spontaneously and continuously. Don’t re-read anything until you reach the end

- Second Draft: A middle grade debut falls around 30–35,000 words. My word count was 50,000 – I had a lot of trimming to do

- Read aloud! You may feel self-conscious, but it helps to spot the snags.

- Build increasingly high stakes for your protagonist

- End each chapter with the beginning of a problem

- Make your characters flawed so we root for them and keep reading

With humour, I learnt to:

- Compose characters from specific people

- Allow their jokes to be squashed – often a ‘forbidden’ joke is funnier than one the other characters like

- Focus on writing character relationships rather than individual characters

- Write to make yourself laugh, not others

Agents and Editors

Scottish Book Trust provided useful advice with looking for agents. Eventually I was represented by the great Tessa David at Peters, Fraser and Dunlop. She gave detailed feedback on my book, sold a three-book deal with Bonnier, and a German edition with DTV. What I learnt from Tessa:

- Trust your editor – most of the time they are right!

- Accept cuts, and don’t get too attached to your writing

- Be confident in the world you have created

- In adventure-comedy, character deaths are tricky

- Pet-death is unthinkable

Editing was fascinating. I learnt to both embrace cuts and to articulate why I wanted to keep something. With revisions, I now enjoy the challenge of replacing a line and hopefully bettering it.

Making comics affected how I wrote middle grade. Used to three-line word balloons, I was often asked to expand something, rather than reduce it. Sometimes though, the accompanying illustration will add clarity. For middle grade, Mark Anchovy is more illustration-heavy.

With production, the paper stock is cheaper than for a graphic novel. This reflects the pricing of middle grade, which in turn reflects the projected sales. Subsequently, I made the illustrations more graphic, to print better than the textured style of my comics.

The series and response

The book’s release coincided with the pandemic, as shops, schools, and festivals closed. But developing Mark Anchovy into a series provided a worthwhile challenge.

The late, great art director Louise Power once advised me against storing up ideas for a rainy day: use them now. With each sequel I sought this, using all my material, as it came. Mark Anchovy’s sister was meant to uncover his secret side-line much later – but I moved this event to book two, which enriched the siblings’ dynamic. Louise’s advice helped me set challenges and build faith in finding solutions. In a sense, this is also what characters do in the story.

The biggest thrill is seeing children read the book. I asked one girl what character she wanted me to draw for her, thinking she’d pick a main character like Mark Anchovy, or Princess Skewer. She asked for the centurion: the villain’s henchman who barely appears (and is fiendish to draw). I loved this request. It reminded me that children are a bit like detectives – they spot things that no one else will.

This article was commissioned as part of our writing for children industry lab. Check out other industry lab resources(this link will open in a new window) for great tips and advice.