Looking for all Articles by Charlie Stickney?

Five things: the differences between writing for TV and comics

Screenwriter and producer Charlie Stickney shares some useful advice for anyone who'd love to adapt their TV treatment into a comic script.

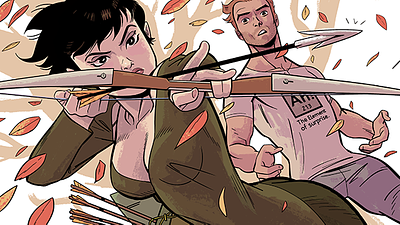

I grew up on comics. They were my first love long before film and way before television. In college I interned at Marvel, and were it not for a job offer with a film company in Los Angeles, my plan had been to move to NYC to embark on a career writing comic books. But things worked out the way they did and I made my career in screenwriting. And I thought that was the way it’d stay, until recently. I was pitching the pilot for a new show, White Ash, and heard not once, not twice but three times something along the lines of 'this would make an amazing comic book' and realised it was time to return to my roots and get to work on an adaptation.

Thankfully, writing a comic book series is very similar in structure and intent to what you do when you break down a television series.

The success of both is hinged upon building an ever-expanding world that continues to generate interesting stories and character arcs. (Unlike a feature film script, which is designed to deliver one complete story.) And television act breaks translate quite nicely to the cliffhangers at the end of an issue of a comic book.

Still, every form of writing is different. And there’s always a learning curve. So if you’re looking to adapt something you’ve written into a comic book, or just write one from scratch, here are five things to keep in mind as you fill up your word balloons.

You only get one shot

One of the most unique attributes of comics is that the story is told through a collection of frozen moments in time. As the writer, it’s imperative that you pick the right ones to best serve your story and maximize the emotional stakes of the scene. You also have to be careful to limit your description of what occurs in the panel to one playable action. If you tell your artist that Carmela throws a vase at Tony, he balls his fists, rage building, then storms out of the room, that can’t be drawn in one picture. That’s three panels at least.

You don’t have actors to bail you out

Try to keep your dialogue as crisp, short and to the point as possible. Unless you’re Shakespeare or Chekhov (and perhaps even then), avoid the monologue. Always remember this is a static medium. You don’t have luxury of having Tom Hiddleston smolder though a paragraph to keep your reader’s attention. A good rule of thumb is to try to limit a panel to no more than forty words combined between whoever is speaking.

Pace and Space isn’t just a basketball term

One of the best ways to create tempo is by using space on a page. It’s a tool that we don’t have in any other form of writing. You can break down action in to many tiny panels, or take a pause with one big splash page. Think of a splash page as the “bullet time” effect in the Matrix.

Pages are your friends; use them

Always keep in mind how what you're writing is going to look on the page. And for that matter, the page opposite it. Try to structure location changes to transition at the end of the page to the top of the next one, rather than in the middle of one.

A picture is worth a thousand words, if it’s the right picture

If you have a good artist, trust them. Don’t overburden the script with descriptive words, trying to micromanage everything. This is a collaborative medium. Let your artist(s) help build the world/have visual input. Let them do best what they do best. I’m very lucky to be working with two responsive artists on White Ash (Conor Hughes and Fin Cramb(this link will open in a new window)) and they make whatever I write look even better than I could have imagined it. Think of your artists like actors: they can add nuance without changing your intention.