Looking for all Articles by Professor Willy Maley?

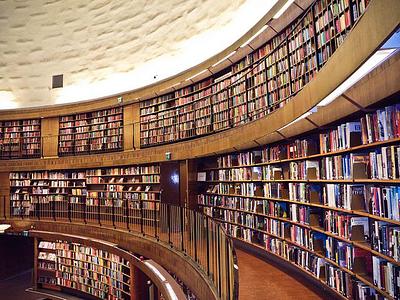

My life in libraries

Willy Maley writes about the libraries that shaped his life

I came to reading through my parents, neither of whom went to university. My father was a manual labourer who brought books home by the bagful from the book exchange at Gilmorehill Bookshop, near Glasgow University. My mother worked in the kitchens in Baird Hall, Strathclyde University’s student hall of residence on Sauchiehall Street. I was introduced at an early age to the treasures in our local library. I still remember the green borrowing card and being sent by my mother to collect a copy of Dombey and Son, a title I can almost taste in that memory of being six or seven years old and going to “get some Dickens”. Years later I discovered Dickens had visited my squalid Dickensian housing estate in the north of Glasgow in December 1847 when it was the site of a mansion house. What novel was being serialized at the time? Dombey and Son.

Borrowing Books

My father, a bricklayer in his latter years, knew we needed more than bread. The bricks and mortar of my education was a weekly ritual, him saying ‘You’ve a week to finish those, then they’re going back to the bookshop’. Books were to be borrowed and loaned, not owned. Read and retained in the mind, not the home. Daddy would present us with a pile of paperbacks and give us a week to read them before they went back to the store. You learn to read pretty fast if the hefty volume in your hands is about to be snatched away. There was no genre or form or period or subject matter that wasn’t thrown in, and certainly no censorship. While I was read books about Blighty by Blyton at school, at home I was immersed in the collected works of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, Louisa M. Alcott, Mario Puzo, Herbert Kastle, Jane Austen, J. T. Edson, Zane Grey, Brian Aldiss, Ray Bradbury, Anthony Burgess and many more. It was a broad-based introduction to literature, or at least to the novel – junk, pulp, classic and cult. I led a double life, like most readers, especially, I would say, working-class readers, excluded from the very world into which I routinely fled. Books spoke to me, but in voices that were not my own.

After School

With insufficient qualifications for university, I worked for three years after leaving school – first for Strathclyde Regional Council Roads Department and then for the Royal Bank of Scotland. When I started my third job with Glasgow City Libraries, I went through the catalogue sampling every available style, including the mandatory Mills & Boon with the sex scene on page 117. Because of this background I’ve never observed any hierarchy between the canonical and the contemporary, the prestigious and the popular. Stephen King’s The Stand is among my favourite books; I recommend his On Writing (2000) to creative writing students, and I’ve supervised a PhD on his fiction.

Alasdair Gray’s Lanark (1981) was a landmark book for me. It was published the year I started Strathclyde University, and was definitely a door-opener for me, and an eye-opener too. Here was someone with a stunningly surreal imagination and a sensuous sense of self and streetlife. When I read in Lanark that nobody notices Glasgow because ‘nobody imagines living there’ I knew it was the truth, not fiction. ‘Imaginatively Glasgow,’ writes Gray, ‘exists as a music-hall song and a few bad novels. That’s all we’ve given to the world outside. It’s all we’ve given to ourselves’. With these words a door swung open. Here was literature and history in the making. Glasgow was imagining itself, engaging in dialogue, talking to itself. The city was finding a voice.

After sitting an extra Higher at night classes, I went to the University of Strathclyde in 1981 to study Librarianship, but failed the course in first year with a mark of 38%. I was given the choice of continuing with my studies at Strathclyde in different subjects and resigning from Glasgow City Libraries, or giving up University altogether and coming back into the libraries as an unqualified library assistant. The library was the best job I’d ever had – it still is – and although I’d only had three jobs, I knew a good thing when I saw it. Then again, my marks for other subjects were good, so after some soul-searching – never found one – I quit my job and continued with English Literature and Politics.

The Future of Libraries

I’ve had close connections with libraries since then. I worked briefly in Jesus College Library at Cambridge University while I was a PhD student there in the late 1980s, and later as writer-in-residence in Milton Library and Royston Library in Glasgow. I’ve had an ongoing connection with the Mitchell Library through Glasgow’s Literary Festival, Aye, Write! Last year I went back to Springburn Library, the first branch I worked in, but the building was closed and its purpose had changed. I think it’s a pity that books and libraries, which were so vital to my own development, seem to be struggling for a breathing-space in the digital age, and the age of austerity. As an academic I still handle books every day, but it’s like they’ve become precious again; not in the way they were to me as a child, but as privileged things that are starting to be out of reach, like they were before public libraries came along. One thing I’d like to see preserved in a future independent Scotland is our great library heritage, damaged by cuts in recent years. In Dickens’s Dombey and Son, Mr Dombey says: ‘I am far from being friendly … to what is called by persons of levelling sentiments, general education. But it is necessary that the inferior classes should continue to be taught to know their position, and to conduct themselves properly.’ I think reading books is an excellent way to forget your position and to learn to talk back to your supposed betters. It worked for me.